The Feel Good Movie of the Year

I have come neither to praise nor bury Mel Gibson’s film “The Passion of the Christ,” but to ask one question: why is this film so popular?

Barring the adage that there’s no accounting for good taste, all the ink already spilled over the film has failed to impress upon me a satisfactory answer. I have to admit that I’m somewhat amazed at what a phenomenon this film has become: I can honestly say that I’ve never seen anything like this in my lifetime. But with all the hand-wringing, casual brush-offs, praise and scorn that has accompanied this brilliantly marketed movie (and that’s what it is folks, a movie), I still was unable to fathom why its juggernaut continued unabated.

Then it struck me: we need to believe this. We have, at our core, not only a desire to believe in a higher power, but to make sense of why the world is so violent and evil. In short, we need apocalyptic beliefs to give us clarity and purpose.

It’s an irony worth pondering over: that we need violent apocalyptic scenarios in order to comfort us and explain suffering and most importantly, to reaffirm our belief in a caring and loving God. In most Christian end-time imagining, an historical event like the Holocaust is just a warm-up for the tribulations that await those “left behind” after the Rapture. When I first learned of some of these beliefs, I couldn’t wrap my mind around why people would almost be longing for this, for extended death and destruction and even more human misery. After all, we have seen the last century fade past, replete with oceans of human blood and succor; mass murder on a scale previously unheard of, worship at the altars of Race and Blood, all hand in hand with an ever growing delight in human depravity. We are the only species on the planet with the ability to wipe out virtually every living thing on earth, and still we say that mankind is the pinnacle of Creation.

Yet in the minds of end-time believers, things become even more debased and all previous human butchery is nothing compared to what awaits us. The mind reels: why? Why do we need this? Why the wide swath of human denial that we long for destruction and murder? There can only be one satisfactory answer: things must become worse in order for God to intervene (finally!) and restore us to our original state. To wipe out evil once and for all. Battle the forces of darkness and triumph over them decisively. Only after this unimaginable suffering will God’s hand be forced and he acts, bringing comfort to those haunted by the stark reality of our existence: we suffer, and God does nothing to end it.

Our apocalyptic beliefs are ultimately our way of exculpating God from his inaction. If God steps in to save us at some point, then all our questions regarding his silence will be squelched: he does care, he does put an end to evil. Yet in thousands of years of human civilization, God has never stopped a war. The heavens have never parted to prevent suffering coming in the form of a massacre, a bombing, or a terrorist attack. God, as usual, remains in his fortress of solitude.

But the silence of God is overbearing to our religious imaginations, and we strive brilliantly to solve the problem ourselves. I’d say that for the ancients, they interpreted bad things happening as a direct result of angering the gods. But ancient man is not the only one to think this: for Judaism and its daughter religions — Christianity and Islam — this notion has remained a fixture in understanding the world down to this day. While we may have a deep, physiological need to believe, we also have an equally powerful need to explain the advent of calamity in our world as a manifestation of God’s will.

How many times have you heard that phrase? “God’s will.” We even use a variant of it when we talk about natural disasters being “acts of God.” On the one hand, it’s amazing that our overall intellectual vocabulary has grown by leaps in bounds in looking at the visible universe and discovering how things work. Conversely, our religious vocabulary remains hopelessly mired in concepts and notions that are so primitive when we try to answer the question of why bad things happen to good people.

Take for example, the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE by the Babylonians. For the first wave of Jewish exiles to Babylon, there was a profound theological crisis: how do we explain the fall of the Holy City, or the burning of the Temple, where the presence of God was enthroned above the cherubim on the Ark of the Covenant? The prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel all found the same answer: it is because of us, because of our sins disaster was wrought. The reality of a foreign power laying siege to Jerusalem and being able to destroy the Temple — previously considered invulnerable to such an attack — needed an explanation that kept God as all-powerful. It is not that God is incapable of defending the city, but that he allowed it to happen. Why? Because of our sin. Thus, Babylon becomes an instrument of the Divine Will and God still manages to remain God.

The solution to this problem (“For our sins we were exiled” goes the standard Jewish lament) did not come easily to a people deeply affected politically and religiously over the destruction of the Temple. In other words, there was no slight of hand, no biblical “sound bite” to make people feel better in a time of need. “How can we sing a song of the Lord on alien soil?” writes the Psalmist, torn away from the one place on earth that assured God’s continuing presence. No matter how much poetry could be composed lamenting the situation, however, questions needed to be answered over how to interpret the situation correctly, and that striving bequeathed a template that would remain locked in our consciousness in explaining how terrible events come to pass. If God is all powerful and acts in history, then he is the Prime Author, and history is nothing more than the unfolding of his inscrutable will. For the later writers of the book of Daniel, Enoch, Tobit, Jubilees, the Apocalypse of Moses and Abraham all the way to the Christian book of Revelation, the theme of how to augur the meaning of history became intertwined with answering the question of evil and how God and his elect would triumph. Without these ingrained beliefs, we are at a loss to explain history and give meaning to catastrophes, natural and man-made.

The massive popularity of “The Passion of the Christ” still plays to that sense. It’s cliché to write that society is in the throes of a general malaise yet right now, we live in a world of increasing uncertainty, and we need something tangible to explain it all. The United States is fighting a “war on terror” that is rather faceless and ethereal. Terrorists hoist spectacular horror on an unsuspecting public. We’re warned they will strike again, because they’re everywhere and nowhere. Worse still, these evildoers may have nuclear, biological and chemical weapons in suitcases. Or not. For Western society, the threat of extremist violence, the dizzying pace of technological advancement, secularization, immigration and the mother of all “ations”, globalization, are leaving marks on a psyche desperately looking for salve.

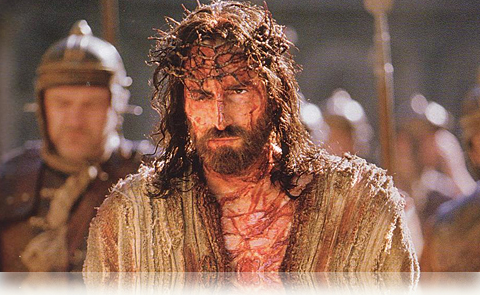

And then along comes a film that serves as an anchor to ideas once considered somewhat archaic. We no longer have a Jesus walking around with an aura (or a British accent): for over an hour, we get to see a half-naked man being flayed alive in excruciating detail and looking like so much raw meat near the end of the proceedings. In presenting such fascistic violence in lurid detail, the battered audience connects to suffering in a way that focusing on the Sermon on the Mount could never have. It puts the reality of evil and human misery right in face of the viewer, and for those who think they’re seeing it “like it really was,” it gives comfort that we are not alone in our pain. Now, instead of believing that God punishes, the viewer can take stock that God is punished along with us. People do not want an abstract discussion of suffering -- they want to see it to know that there’s an answer for it, because the times we live in are so violent and frightening. Anything else is reeks of a cop out. The extended gore is a catharsis of sorts, relieved by the original Hollywood ending: the resurrection (brief as it is). So even the worst episodes come to pass and good triumphs. That is, I feel, the true essence of why the film is so popular, and why it’s bringing in viewers for a second or third helping.

In other words, “The Passion of the Christ” is the right movie at the right time.